Quick Reference Guide

Commit to a Housing First Strategy and Plan

Housing types (group homes, micro-communities, and individual accommodations) should be diverse – there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and policy should reflect that.

Community planning and diversification of housing types must be thought through because concentrating large numbers of formerly homeless in one area might create unnecessary stigma in those areas.

Services offered (mental health, healthcare, career help, etc.) need to be expansive, and they should be factored into the bids for who will run the facilities and into the cost of these facilities.

2-4-year program durations with mandatory reviews, both qualitative and quantitative, to address any areas for improvement and incorporate those areas into the next iteration

Continued building and maintenance costs need to be considered. The initial investment will be high, and while savings will come, it will not be immediate, and those costs need to be internalized so that the program can grow and flourish.

Strong government coordination with NGO help needs to be the model to reduce fractured feeling of care and provide clarity to those needing support.

Provide Work for Housing Options

Work for housing options should run in tandem with housing first to provide additional support and options while housing first gains traction.

Nightly housing or a “safe zone” could be provided for working with a sanctioned job service.

One-off sites for tents or vehicles to stay in certain areas or along highways in exchange for keeping these areas clean and maintained

Utilize the Skills and Knowledge Within the Homeless Communities

Awareness and culture tours on drug use, immigration and refugee issues, and homelessness around Denver could be a great way to provide skills to these groups as well as much-needed awareness for the rest of the community

Jobs that focus on cleaning, repairing, and maintaining bike rentals or other facilities like public restrooms, untamed land, or parks.

Introduction

We look through people. I look through people. Even when writing articles or taking photos, I’m not always seeing the way I could be.

And it’s nothing personal. I don’t always want to know what you’re selling. I don’t necessarily want to hear what you’re asking. I don’t want to tip you when you’re playing (though I usually do). Some days, I just don’t want to engage.

But isn’t there an irony here – saying that it’s nothing personal?

As Neil deGrasse Tyson said… “We take better care of our Cats & Dogs than we do of homeless humans on the street. If we serve as pets to Aliens, might they take better care of us than we ever will of ourselves?”

This statement, which I’ve heard him say multiple times in various ways, feels very real and very hard to hear.

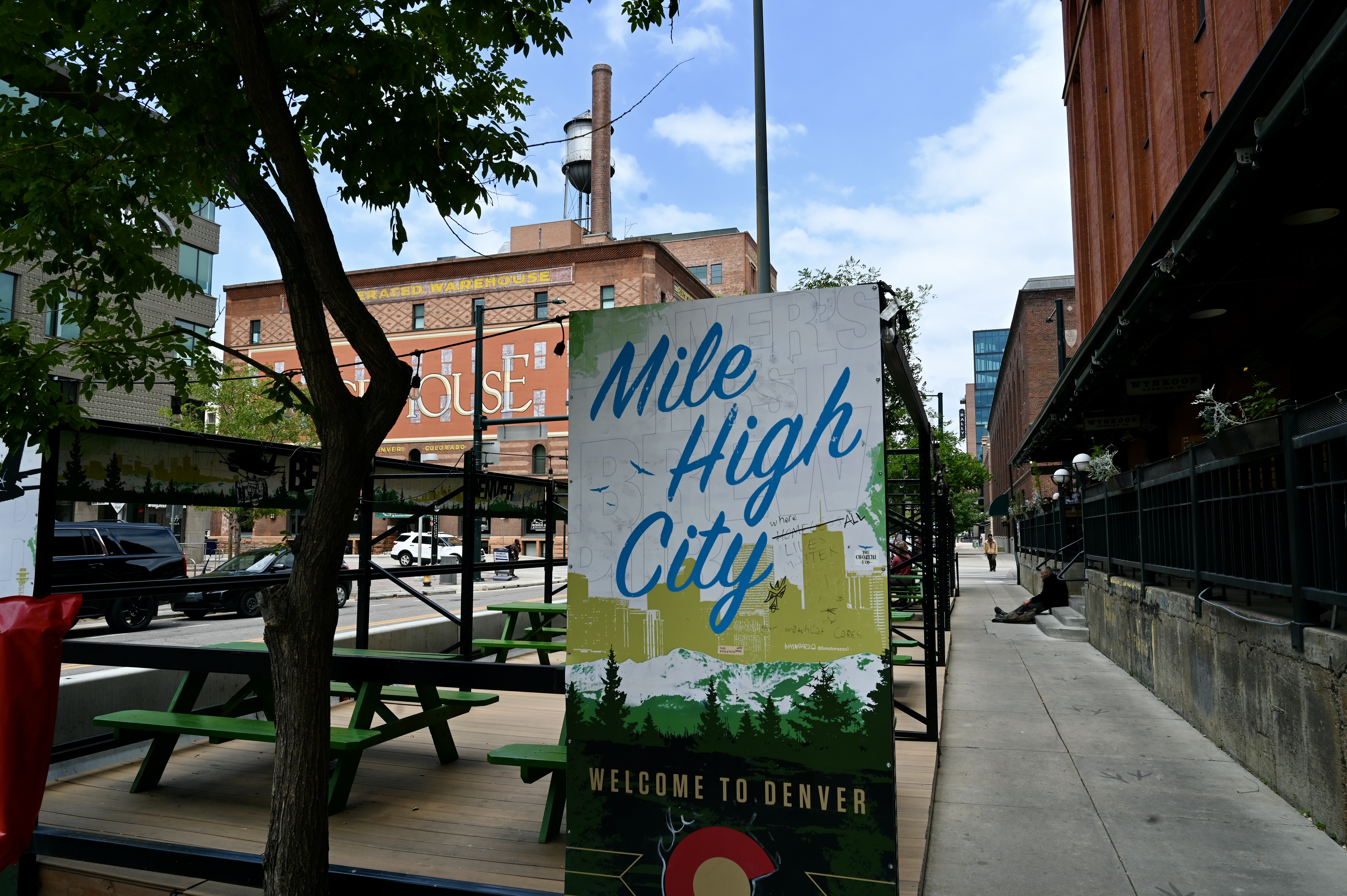

I’ve barely walked 4 miles in Denver’s overpriced, beautiful, and endlessly changing downtown center, and I’ve seen three or four people yelling at themselves or throwing things. I’ve seen one man pass out and need medical assistance. And I’ve seen 4-5 people sleeping on sidewalks while countless others wait for a place to sleep.

I took the Denver Light Rail from Littleton to the convention center (a roughly 30-minute train ride), and I saw two tent clusters as we rolled past warehouses and unclaimed land and numerous people hanging out at each stop who had no intention of getting on, they just wanted somewhere they could get under cover quickly.

No one can live here and believe we are on the right track to helping those without homes, and the statistics would seem to agree. Right now, the Denver metro area has the 10th highest homeless population in the country, with nightly numbers at roughly 6,884. That total is hard to compare, however, because of the complexities surrounding just what homelessness is.

No standard definition of homelessness exists within the US, let alone the world. The current numbers result from each city and country having differing ways of counting, times to count (day or night), and definitions of whom to count. This reality means that many numbers are better thought of in a range than a concrete fact. For many reasons, these estimates are likely lower than the actual numbers.

Whom to count is tricky since being homeless means different things to different people. For some, it means eviction with no car, no plan B, and cold nights spent in parks or on stoops. This is known as “sleeping rough.”

For others, it means a Sprinter van that is cheaper than applying for an overpriced apartment that requires a deposit with two months of rent upfront. Many homeless people are couch surfers who bop between friends, family, and shelters. And many more live in housing that is unsafe or inadequate.

Those outside roughing it are the ones who are the most visible and require support to survive. But they are not the whole population, and solutions to alleviate or end homelessness should not be tailored just to them. Sometimes homelessness is a choice, and we need to find out why.

The label homeless is marred with images of lazy insane people hitting their heads or running through traffic, screaming and lessening the safety of everyone around them. In reality, that’s just a fraction – but arguably, it’s one of the more visible factions which hampers a societal shift in the narrative towards empathy and inclusivity.

There is diversity in the homeless communities, just like every other apparatus we ascribe to people. Some are addicts, some are disabled, and some are mentally unwell. And then there are a whole host of people on the streets who are of sound mind and body and, for one reason or another, wound up there and are trying to make the best of it. They clean up, dress well, and may have a job. They are the invisible population that does enough not to be a statistic while trying to get themselves together.

This invisible population is especially prevalent in countries such as Japan, where the official number of homeless flirts with zero year after year. It is shameful to admit that you have no home, so instead, you find a place to shower and shave, you put yourself together from wherever you managed to crash the night before, and you clock in for your shift.

The complexity only grows once you factor in refugees and displaced people. How do you separate homelessness from refugee and asylum seekers currently sleeping on sidewalks, in bus stations, and in other central locations around the US? Where is that line?

Do we give refugees homes or host families? Do we turn them away? Those we let in, do we pawn them off onto another city? New York City (NYC) declared a State of Emergency for its migrant populations and is building entire shelters to try and accommodate all of the refugees flying into or getting bussed to the city. NYC Mayor Eric Adams admits that the city needs additional state and federal funding for the migrants because the city is “past our breaking point.”

Chicago similarly declared a State of Emergency for its migrant populations.

Do we count migrants and refugees in the overall homeless numbers? Is it fair that caring for them may distract from caring for our homeless? Should refugees that fought so hard to get to a place of safety deserve to be sleeping on the streets with their children?

The UN definition of homeless covers all of these groups. It makes the definition very long and the impacted population very large:

Homeless populations include, “Persons living in the streets, in open spaces or cars; persons living in temporary emergency accommodation, in women’s shelters, in camps or other temporary accommodation provided to internally displaced persons, refugees or migrants; and persons living in severely inadequate and insecure housing, such as residents of informal settlements.”

https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-housing/homelessness-and-human-rights#homelessness

Homelessness is a messy, complicated, steaming pile of reality about the stakes and priorities of this society, and it is compounded by hundreds of other social dilemmas. If the cause can’t be clearly conveyed, how can a solution be?

I’m writing this article because there is a significant homeless population in Denver, which is not an isolated phenomenon in this country. Mayors across the US have declared emergencies on growing homeless and refugee populations in the past year. A few months ago, Denver joined those ranks.

So I set out to see what other countries are trying that could be implemented in Colorado.

Setting the Stage

Denver is a cacophony of different messages and takeaways. It is a city that continues to grasp at a booming tourist industry and flirts with a progressive ideology—the sanctuary city in practice, if not in name.

The darling of active hikers and bombastic snowboarders. Of outdoor enthusiasts and beer snobs. To some, it is the pearl of the cities that are speckled between Washington DC and San Francisco. The metropolitan center of the Midwest. More real. Less perfect. Nostalgia mixing with reality.

Denver is a moral grey zone all of its own. It is a vast sea of potential and gentrification. Of luxury apartment buildings and a high cost of living. It has a history and soul. There is art and music on the streets as you explore them, but as with any city, the life and culture and food and fusion are all right next to an ally that smells with a dead-end sign proudly standing at the mouth, warding off the intrepid with no noses. There are still problems here.

Very few places can boast a winning record with homeless populations. Alaska is currently contemplating a new practice that would send its homeless on a one-way trip to “warmer climates” because it would save them money spent on keeping people warm and fed. The Biden administration is working with six cities and states, including Seattle and California, to try and increase federal help for people without homes.

New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles mayors started brainstorming solutions with cities like Houston, which has remarkably decreased its homeless population over the past decade. Even Colorado leaders traveled down to Houston last year in 2022 to see what their policies look like.

We may have gotten the message because Mayor Johnson is devising a 4-point plan that would focus on the following four objectives:

- Moving unhoused people into housing units through rapid rehousing or access to available apartments

- Calling on landlords and property owners to partner to get people access

- Hotel conversions

- Looking at parcels of land in the city to open micro-communities, like tiny homes, to give people shelter, housing, and resources like addiction help and workforce training

The goal is to get 1,000 people into homes by the end of this year. This solution is not foolproof or complete but is a step in the right direction. All the boxes look like they’re being checked, and because of the emergency declaration that the mayor made, all these things might be able to happen relatively quickly.

However, amid some very promising policies, the Mayor also green-lit cleaning out homeless encampments again.

Making people move their tents because it’s an eye sore, seizing people’s possessions, or taking people to jail are not viable solutions. These actions will not help the problem and honestly, they make things a whole lot worse because it erodes the trust needed for future policies to be effective. People are not cans that you can kick down the road, and allowing the clearing of encampments while admitting that they have no other alternative or any place to go is irresponsible.

Denver could be part of a better way of thinking about homeless communities and what solutions could be. But for many reasons, this will be an uphill battle.

A type of housing first emerged in Denver in 2016 with the Denver Supportive Housing Social Impact Bond Initiative (SIB), which worked with investors to buy bonds that would go into a fund to house homeless populations with a history of criminal charges. The concept of Housing First will be discussed in greater length below, but for now, know that the program was rated as effective in reducing repeat offenses and boasted an increase in people seeking support services. 86% of people were still housed after the first year. It was only slotted to run for five years while a comprehensive study took place to analyze the results.

In 2019 and 2022, Denver again implemented a small housing-first initiative called Housing to Health which aimed to get chronically homeless individuals into housing with a history of mental health or behavioral issues. The 2022 iteration sought to house 125 people—a small but hopefully doable amount.

A cultural shift in how we talk about homelessness is not easy. Having a solution for the “problem of homelessness” seems like a lose-lose for politicians and media alike. It’s a long-term game – not something we can alleviate in an election cycle, and it is not a fix that can be conveyed clearly in a 10-second sound bite on CNN.

For decades Denver’s track record with homelessness has been a yo-yo of carrot-and-stick policies aimed at helping people experiencing homelessness and deterring places for them to sleep outside of shelters. This Westword article does a great job of exploring that vacillation in its breakdown of the history of homeless policy in Colorado.

For the last 11 years, Denver has enforced a policy called the “Denver Camping Ban” that then-Mayor Michael Hancock signed into law. Interestingly, the camping ban was just as much a response to the Occupy Movement in 2011 as to homelessness in Denver. It allowed for random sweeps of homeless camps that could result in tents, sleeping bags, and other possessions being “seized” with very little notice.

In 2020, COVID caused a reassessment of the ban, which resulted in the approval of “Safe Camping Sites” opening up within Denver. Homeless people could start to camp in designated locations safely, but anyone still found to be camping or sleeping outside of those safe sites could still be subjected to random sweeps or fines. The legality of the sweeps was brought to the courts several times over disagreements about whether Denver followed the rules.

The age-old dilemmas played out again and again. Whether to use citations vs. safety net, fear vs. empathy. Whether Denver will stand with people experiencing homelessness by providing resources instead of taking away property or whether they will slip back into enforcing the camping ban by destroying temporary housing and sending those people to jail.

With all of that said, Colorado is also a place of great innovation and creative ideas on helping those experiencing homelessness include paying homeless people a no-strings-attached monthly stipend, building tiny homes for unhoused veterans, and an instant-gratification twist on the Staircase Model of homeless policy where the more milestones reached, the better shelter accommodations are received.

It needs to be said that many non-profits, NGOs, and civically minded people have and will continue to care for the homeless populations of Colorado. Organizations like the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless provide homes, healthcare, and other services to help people in need. I do not have the time nor space to discuss each one or detail their fantastic work, but if you would like to learn more, here is a list of nonprofits working with those without housing in Denver. And honestly, just run a simple Google search for “Denver, Homeless, Non-Profit,” and you’ll see the breadth of support.

While uplifting, this does contribute to a fractured feeling of care that left me confused, and I’m sure it does so for many.

Ideally, implementing some of the following international ideas can act as a buffer while Denver steps up its shift to Housing First, and while Colorado fleshes out its homeless policies.

Global Insights

Currently, there are an estimated 100 million people without homes throughout the world.

“By 2030, UN-Habitat estimates that 3 billion people, about 40 per cent of the world’s population, will need access to adequate housing.”

https://unhabitat.org/topic/housing

Say what you will about Denver policies or even United States policies, but it’s still good to remember that things can always get worse.

The US is in the middle of the pack regarding estimated worldwide homeless rates, with roughly 500,000 homeless per night. Nigeria is estimated to have the largest homeless population, with some counts seeing 24 million people homeless per night, much of that due to inadequate and illegal housing that people banded together to provide for themselves. Again, as stated before, take all these numbers and statistics with a grain of salt.

Worldwide you can see the same issues playing out from city to city. Income inequality leads to an inability to keep up with an increased cost of living. High competition for jobs means that some people just won’t be able to find work; or if they do, it might be far below their experience level or education. Luxury apartments that constantly replace affordable or subsidized housing prevent realistic living options for many.

Even places with notably low numbers of homeless, such as Hong Kong, struggle to maintain enough affordable housing options in the aftermath of Covid and rising unemployment.

England now boasts the highest rise in homelessness in 25 years, mainly due to housing shortages. UK charities advocate for their country to follow the Japanese and Finnish models, utilizing robust and adaptable government strategies and NGO cooperation.

With that recommendation in mind, I wanted to look at both country’s policies.

Finland

In 2019, Finland was the only European country where the number of people without a home was falling. The road to success, however, was not a fast one.

In 2008 Finland started a program based on the idea of “Housing First,” which focuses on getting homeless people into homes instead of forcing them to be “better” before being awarded a home.

The predominant idea in Finland before 2008 was similar to most countries where a person was expected to gradually move up the moral ladder to get a permanent place to live. This is called the “staircase model.” Every triumph, such as getting a job or getting off drugs, would put you one step closer to getting an apartment or a house.

The Housing First model flipped that on its head.

The thinking was, how can a person be expected to fix themselves when they have no idea where they may be staying that night?

All people want a home, somewhere safe, even if it’s to sleep, keep possessions, or get high. People want a home base – somewhere to return to at night so they don’t have to worry if this park is heavily patrolled or if this parking spot is available.

Change for many people takes money, commitment, and planning. Change takes resources and support, things that many homeless do not have. How can you get yourself into an apartment with horrible credit and a mountain of debt? How many jobs can you get without a home address?

The Housing First idea came from a New Yorker called Sam Tsemberis, who developed this model to fit the needs of the homeless people on the streets of NYC. It has been implemented in some capacity in cities worldwide with various degrees of success.

If interested, this article explains the differences between the Finnish model and the original housing first model and what Finland did well.

The four principles of Finlands Housing First are:

- Housing enables independent lives

- Respect of choice (both in housing types and lifestyle choices)

- Rehabilitation and empowerment of the resident

- Integration into the community and society

Once Finland adopted housing first, it started buying up old shelters, flats, and plots of land to act as homeless housing centers, and it partnered with NGOs to provide services and research. Finland is doing a dual program of individual housing options (to lessen stigma and provide independence) and group homes (for those who may want more support), and each has pros and cons.

“Since its launch in 2008, the number of long-term homeless people in Finland has fallen by more than 35%.”

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jun/03/its-a-miracle-helsinkis-radical-solution-to-homelessness.

One of the most promising aspects of the Finnish adaptation to the housing first model is how they turned it into an almost living and breathing policy that constantly seeks to adapt and shift to meet demand. There have been four iterations of the Finnish housing first program. Each segment lasts three years and has something specific that it’s trying to focus on based on the reviews and assessments of the previous model.

The first two models focused on building homes and reducing long-term homelessness, the third sought to prevent homelessness through various support systems to get people right into housing, and the fourth and current model aims to institutionalize housing first and strengthen local municipalities working with homeless populations.

The idea is to provide each person access to mental health and life services. The expectation for most housing first units is that getting sober or clean is not a requirement for the program. However, some rules are enforced, so most people are placed on a 3-month trial period to ensure it works for all parties.

This massive initiative by Finland was a costly undertaking. Some estimates put spending at €270 million (that’s $294 million) on the initial build and redesign of the apartments. However, studies have shown that over the course of a year, Finland has been saving an average of €15,000 to €21,000 per homeless person in the program on healthcare, social services, and criminal justice costs. That is a massive amount of savings that can be reinvested into the housing first initiative.

The Finish governments largely had the political will and infrastructure to support this significant project getting underway quickly, arguably in contrast to Colorado.

For instance, one in seven residents of the Finish capital lives in “city-owned housing.” The government of Helsinki owns its own construction company and 70 percent of the land within its borders. Finally, the government is heavily involved in city planning. It works to ensure that each region of the city comprises a combination of social housing, subsidized housing, and private housing to mitigate socially segregating segments of the population.

This is part of the uphill battle that Colorado will face because simply doing housing first in part will likely not adequately help. The social stigmas of large government social welfare projects must be overcome to do housing first right.

Austria

Unlike the other two countries on this list, Austria has no national homeless initiative. Instead, it has fallen on individual cities such as Vienna, which has been praised in recent years for some of its policies geared at moving to no homelessness.

Like other cities, Vienna has adopted the housing first model and has implemented the concept in a tailored way to fit their city:

The key to the city’s success comes from its protection of open space, transit-centered development, rent control and a focus on building neighborhoods with mixed ethnic, age and income communities. On top of that, roughly $700 million goes to government-subsidized “social housing,” which shelters 60% of the capital’s population. This results in a combination of non-market and market affordable housing.

https://borgenproject.org/homelessness-in-austria/

I highly encourage you to look more at Vienna’s Housing First program, but here I would like to mention another initiative within the city that is genius, and I can see a lot of potential with it: Educational tourism.

Shade Tours has found a way to bring awareness to the community and tourists alike while also providing finances and skills to people who want them. They offer tours that focus on “poverty and homelessness,” “refugees and integration,” and drugs and addiction.”

The concept is simple. Homeless people are experts on being homeless. Refugees are experts on being refugees. Drug users are experts on being drug users. And people from all over will be curious to hear what these communities have to say. Shades Tours hires these experts to provide tours of Vienna to give a unique perspective on issues within Vienna.

The goal is to reintegrate vulnerable populations back into society and the labor market by offering them jobs as guides who take people on tours focusing on real issues within the city. The icing on top is the knowledge and empathy that may come from tours such as these.

Any initiative that brings the power of knowledge and awareness and combines it with building self-confidence and financial opportunities is a no-brainer. Denver has plenty of experts on issues such as these and arguably more if it gets creative. Denver also has a ton of open-minded people who would likely flock to learn more about the city they have come to love. The uniqueness of the experience should also be recognized as a selling point.

Did I mention that Shades Tours has the option to franchise?

Japan

Japan has had one of the lowest homeless numbers in the world for years. In 2022, it was estimated that 862 people, mostly older men, were on the streets of Tokyo throughout the day. At night, roughly 1,500-2,000 homeless are thought to be sleeping rough. Tokyo is an enormous city with millions of people, so they are clearly doing some things well.

No discussion of Japanese policies on homelessness would be complete without at least mentioning the economic bust of the 1990s, which sent shock waves throughout Japan and much of Asia. By 2003 (the first year these records were kept), an estimated 25,000 people were sleeping rough.

One of the programs primarily credited as being instrumental in easing the homeless population over the past 20 years has been the “livelihood protection” program.

While it is not without controversy, the livelihood protection program aims to provide money to people with no outside support so that they can get an apartment and other basic needs. It also tries to keep people within their homes if they cannot afford them.

Labor and Welfare centers are another bridge that acts as a one-stop shop of support and job opportunities, and they are also available throughout Japan. Here is a link to the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare website (in English).

Some aid also came about organically. Osaka hostel owners banded together to start providing housing for the homeless day laborers who work with the labor and welfare centers. In December of 2021, 10,000-day laborers got their rooms for free because of those hostel owners, which was a record number.

The idea that you can work for your shelter is something that Denver needs to consider as part of a multifaceted plan to combat homelessness in all of its iterations. It is a powerful concept that will be explored more later.

Japan is also known for getting it’s mentally ill into places of support so they are not left out on the streets. However, there are some criticisms that mental health care at these institutions is not up to the same standards as Japan’s healthcare system. Japan, it should be noted, routinely has high rates of suicide.

Cultural aspects of Japan, as well as ongoing policies like Japan’s strict laws on drugs and begging, both of which are illegal, also provide some light on the low levels of homelessness in Japan. Drugs, especially fentanyl, and heroin, have contributed to the complexity of homelessness in the US, but in Japan, very few people try drugs other than alcohol. Begging is illegal, but some homeless can get money by finding things in the trash to sell.

Tokyo has routinely made parks and other outdoor areas harder to sleep or stay in, which further limited the options for people experiencing homelessness. It has been argued that many of Japan’s programs for its homeless populations are more about shoring up the image of beauty and making society better than about helping the people experiencing homelessness.

The idea that homelessness was self-inflicted is pervasive, and there is great stigma in such “behavior.” There is a great shame, especially for men, associated with not having a home or the ability to be self-sufficient, and many believe that the problems originate from gambling debts or other self-perpetuating issues.

This stigma creates a hidden homeless population – where people choose not to seek help from the government or their families. Instead, they try to find ways to work through the problem themselves, and their numbers are likely not counted in the national narratives.

Enter the cyber cafe. A cheap room that you can pay for by the hour and has internet. Many people will use these tiny rooms to sleep, shower, and work as needed. They are not “roughing it,” but they do not have a home base. They are called the “internet cafe refugees,” and in Tokyo, their estimation was 4,000 in 2017.

Adults and youths who use these kinds of options are hard to track. They do not look homeless, and they may not require services. Many have full or part-time jobs and may bounce between staying with family, renting rooms in cyber cafes, and passing the time in 24-hour restaurants.

However, the impact of these populations could be felt in 2020 when cafes and restaurants closed due to Covid; the Tokyo government moved to get thousands of hotel rooms so that the internet cafe refugees didn’t end up on the street.

Having places like cyber cafes for people to rent for hours at a time might be a good idea for Colorado in the interim, but other ideas from Japan are worth considering.

One such innovation is hiring homeless people to staff Bike Sharing facilities and repair bikes. Many homeless in Japan use bikes to gather trash, such as cans that they can then sell, so many were already comfortable with bikes and knew how to fix them up.

Kawaguchi Kana is the brainchild of this initiative, and she has also built up one-stop centers for homeless people to get support and is also working with homeless youths.

I would love to see a combination of working for a place to stay in Colorado, utilizing expertise for jobs, and providing cheap shelter alternatives. It’s not perfect and won’t solve all homelessness, but it could be a good bridge while Denver adopts a more housing-first mentality.

Local Results

Colorado, specifically Denver, cannot simply stick people, some of whom are unaccustomed to sleeping inside, into an apartment and call it a win. It is a constant endeavor to provide the services and develop trust, both in the homeless communities, which have years of reasons to distrust such programs, but also within the broader Denver community.

Denver policymakers need to make sure that if they are serious about utilizing the housing first model, they think through things like continued building, diversifying neighborhoods enough to prevent additional class segregation, and the need for resources like service providers, mental health providers, and career/life coaches.

It will take a community to make this work, and Denver has that. But it’s going to require a bit of planning as well.

Housing First has been rolled out to many cities worldwide, and many have seen some success. However, consideration needs to be given to how housing should be rolled out in each city. Two areas were identified as needing additional pre-planning in a 2016 European Commission report regarding cities with mixed results with the program.

The first area was the level of support the program receives – if you don’t initially invest, it will be hard to reap the rewards. The second area was deciding whether program recipients should be housed in the same building or separately. Group homes allow for increased access to community resources and services, but such buildings may be stigmatized. Individual housing options can create a sense of independence but, admittedly, offer less support. The Finnish model has adopted both.

Denver will need to decide what to adopt as it gains momentum. The SIB program from 2016-2021 was a fantastic way to dip the toe in, but in the future, the duration of the program should be cut down to two-four years for evaluation based on the success of the adaptability of the Finnish program. It should be followed by another program that considers those lessons learned for the next iteration.

Juha Kaakinen, the CEO of the Finnish affordable rental housing provider Y-Foundation, argues that most housing-first programs fail because there is insufficient support for the people in the program. Still, he acknowledges that there is a balance between individual needs and communal solutions and that there is no one solution for everyone.

I believe it prudent that we should listen to him and offer many types of housing to try and tailor enough programs to fit every individual’s needs. This cannot be done by the state alone. It will require non-profits and NGOs to help stitch it all together.

Finally, I’d like to see various other programs start springing up, such as the micro-communities Mike Johnson called for, the employment opportunities for homeless people such as cultural tours and bike programs, and various work-for-housing programs like those in Osaka, Japan. That scenario came about because of a community of compassionate people; I’d like research to be done to try and achieve that at a state or city level.

Something as simple as having a program where people could clean up sections of roadways or highways around their tent in exchange for not being forced to move might be an easy place to start. If nothing else, it lets people stay in a single location for a while with some security and gives them a job. Not too much of a cost for a clean road.

Denver, and Colorado more broadly, is heading towards better policies, but I see room for growth. I look forward to seeing what has yet to come.

Resources

For Those Who Want a Deeper Look

- A fantastic policy paper breaking down Finland’s Housing First: https://academic.oup.com/book/44441/chapter/376664562

- Denver’s Housing and Homeless Guide: https://denvergov.org/Community/Housing/Housing-Homelessness-Guide

- Denver’s Shelters and Services Guide: https://www.denvergov.org/content/dam/denvergov/Portals/692/documents/Denvers_Road_Home/denver-shelters-services-guide-web.pdf

New Articles and Announcements from Colorado

- Polis Executive Order on Housing 8/21/23

- Denver Micro-Communities

- Johnson Clears Out Another Camp 8/23/23

- After homeless sweep, dozens moved to new Denver shelter 9/26/23

- Man describes first night in shelter after Denver homeless encampment sweep 9/26/23

- “Cash is freedom”: Denver experiment with basic income for homeless gets City Council support 10/7/23

- Denver breaks ground on 120-home micro-community in Overland neighborhood 10/12/23

Not All Solutions Can Be Found Abroad